A Forest Sounds Like a Ship at Sea:

Manifest Equity

Day 12: Remote Residency at Uillinn: West Cork Arts Centre, Skibbereen, Ireland, 7/18/22 to 8/13/22, Maria Driscoll McMahon checking in from New York State

|

| "Progress" (The Advance of Civilization), Asher Brown Durand, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

In this painting by Hudson River School painter, Asher Brown Durand, "manifest destiny" is ostensibly advanced. It was, after all, commissioned by a railway administrator. And yet, I can't help but to read a (too) subtle critique in the painting. In the right of the work, colonial expansion and development is depicted in its many forms. We see smoke stacks, bridges, roads, busy colonists farming and tending "livestock."

We also see deforestation - loss of habitat - which equates with loss of inhabitants. This is said to be "progress."

Gone will be the wolf. Gone will be the mountain lion, Gone will be the forests. Gone will be the chestnut tree.

Most tragically, gone will be human beings who called their ancestral land "home."

To the left of the painting, we see First Nations people watching the scene from on high. (In retrospect, was this not the moral higher ground?)

A common trope of the Hudson River School painters was to paint the tree stump as allegory. Many times the stump has been cut indicating that a tree has been "felled," representing development and "civilization." In the case of a stump that has been "blasted," the symbolism is for a tree that has fallen naturally.

In this painting, stumps have been both cut and "blasted." Trees on the right have been (almost obscenely) turned into telegraph poles. Trees to the left seem to have fallen naturally. The impact on the environment left by First Nations is comparatively minimal as indigenous people lived (and live) very much in harmony with the natural world. For some First Nations, the North American continent was called "Turtle Island."

Thomas Cole, the founder of the Hudson River School painters, aspired to capture the rapidly vanishing landscape in oil on canvas. He was so dismayed by "the ravages of the axe," he dedicated his life to painting and writing about it as in the poem The Lament of the Forest. In a letter to a friend, he cast "maledictions" upon the "tree-destroyers" who were "cutting down all the trees in the beautiful valley on which I have looked so often with a loving eye."

Meanwhile, while technological advancement has brought many gifts to humankind, it has also killed and destroyed and threatens to keep doing so if we continue to fail to learn from the past, to try to make things as right and just for the present, and listen to the teaching of representatives of indigenous cultures - past and present - many who call us to live in harmony with the natural world which sustains us all. We do these things or pay - not only with our own lives - but the lives of many of the beings on this planet.

|

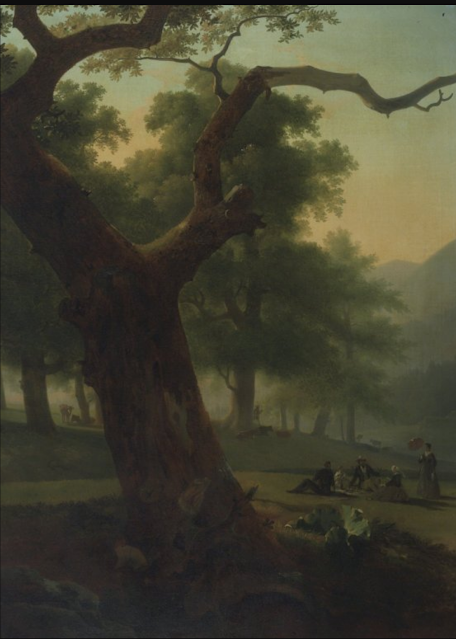

| Picnic in the Forest, 1840, Brooklyn Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

.jpeg)